Twitter followers may have noticed a switch in focus with the switch in locale. The UK has some of the richest and most accessible heritage in the world (a statement which, unlike the rest of this blog, I feel somewhat qualified to assert), and recently I’ve been escaping pandemics and invasions into its quiet and unassuming embrace.

In particular, having spent several years tracking down scarce remnants of China’s older dynasties, I’ve started a similar project with the few (but more than you might think!) remains of Britain’s Anglo-Saxon period – about 450 CE – 1066 CE.

I will be sharing more on as the project evolves, but today wanted to jot down some thoughts on a more obscure church, and how a visit led to and exposed some fascinating questions.

(As with all my blogs – I am an amateur and reliant on much cleverer scholars, cited at the end; any mistakes are entirely my own)

A Great Dane

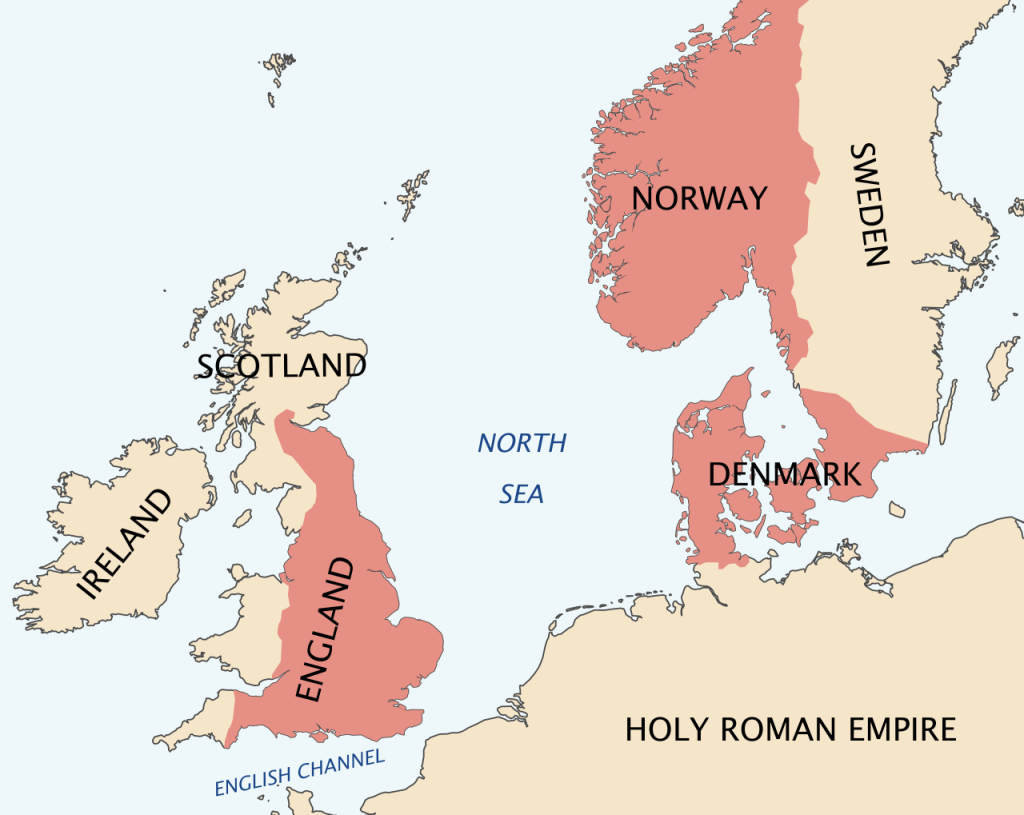

It’s January 1017, and the Danish Prince Cnut has taken the British throne – ruling over a united kingdom of Saxons and Danes after centuries of Viking raids. His hegemony – soon adding Denmark and Norway to a ’North Sea Empire’ – will be short lived, replaced by a Saxon revival under Edward the Confessor before William the Bastard will claim victory 50 years later at Hastings.

Cnut’s accession had been secured by a crushing victory over the Saxon King Edmund Ironside at the Battle of Assandum the previous October. To commemorate the battle Cnut constructed a memorial Minster church at its site, now often – but not universally – located in Ashingdon near the Essex coast. Today a church, St Andrews, sits atop the village, but there is scant trace of 11th century material to associate with Cnut’s foundation.

A curious connection

About 40 miles north-west are the tiny villages (pops. 893 and 332) of Ashdon and Hadstock. The former, with its similar name, has been suggested as an alternate site for Assandum. Circumstantial evidence supports this; reports of ancient bodies churned up by Victorians building a railway cutting at nearby ’Red Fields’, located on the strategic Icknield Way.

But more intriguing hints come from Hadstock’s church of St Botolph, which has a pedigree far longer than anything at Ashingdon. I stumbled into the churchyard after a surprisingly gruelling day hiking the Icknield Way – there are almost a half dozen Saxon churches in this part of Essex. First impressions are of its size, entirely out of proportion with the tiny village over which it presides, and a higgldey-piggldey jumble of restorations – including a hideous Victorian attempt to render the outside in concrete. On closer inspection, the massive church’s nave and transepts have clear diagnostic features for the pre-Norman church I’d come to look for: quoins (corner stones) made from large, alternating long and short blocks; small, narrow windows to reduce draughts into the ancient church; and, inside, mouldings on the arch columns and door frames lacking the grandeur of Norman artifice but instead full of a more intimate vernacular charm.

So could this actually be Cnut’s church – if so, one of but a handful of surviving Scandinavian-built buildings in England?

Turning back the tide

One of the joys of my new hobby is the palimpsest comprising almost every British church; centuries of accretions as parishioners, Bishops, and Kings have patched up, extended, or ’renovated’ to suit their own eye. Hadstock is a prime example – even a neophyte like me can spot pointed arches in the nave (a sure sign they’re 13th century gothic, or later); a Victorian chancel; and a west tower crookedly joined to the nave, betraying it as a later addition.

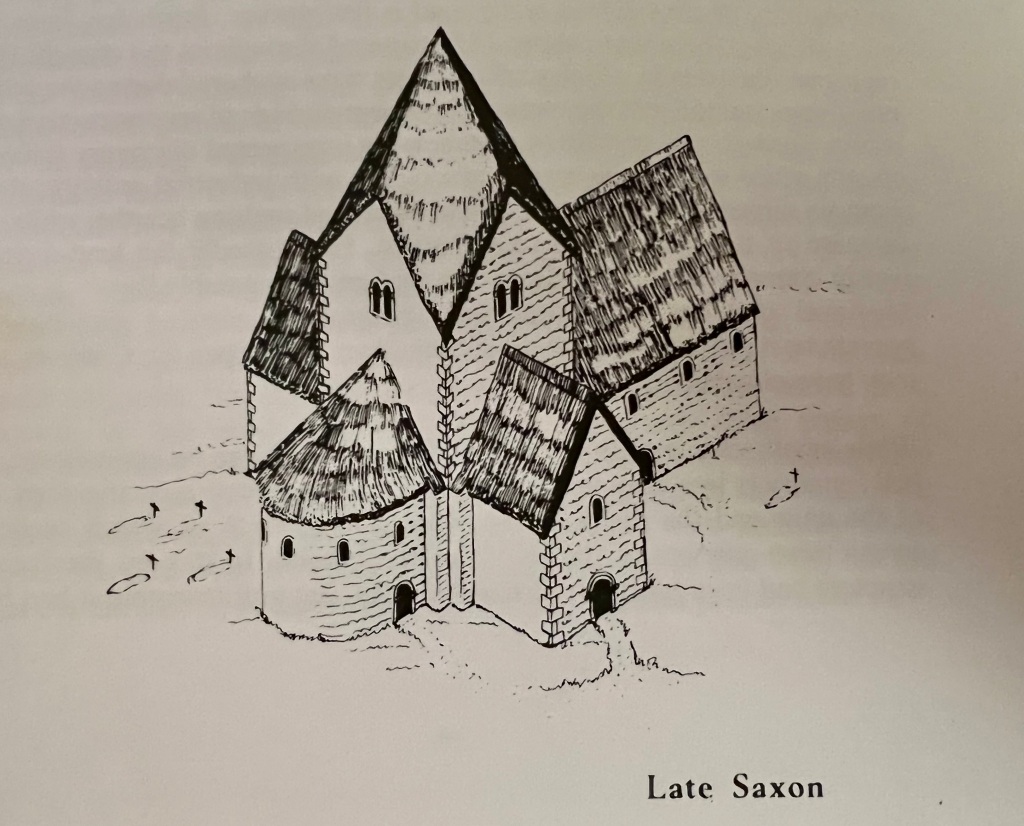

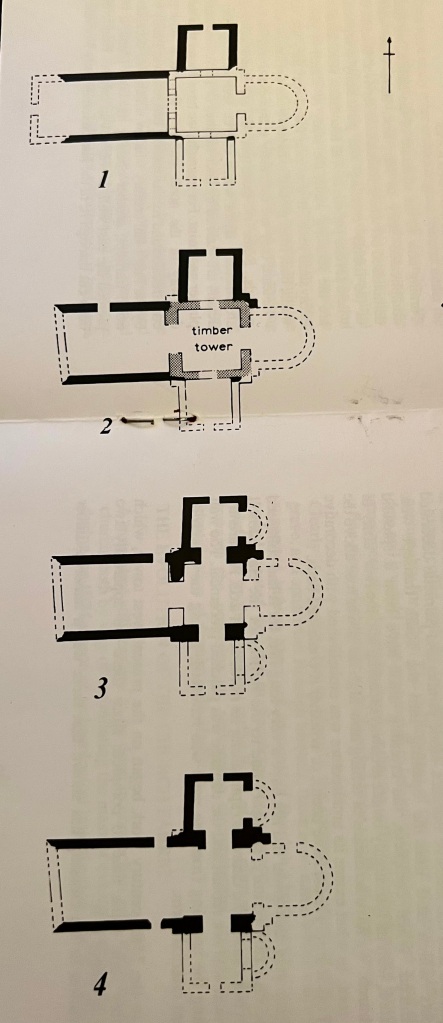

Archaeological excavation in 1973 prised apart this story. While not settling the debate as to whether this is Cnut’s Minster – certainty maybe now unknowable – supporting evidence was adduced. The church’s nave and north transept are Saxon, probably raised to their current height in a large building campaign in the early 11th century – the right date for Cnut. This built a grand stone tower over a crossing arch – perhaps similar to the contemporaneous Stow Minster near Lincoln – which collapsed by the mid-13th century. Replacement arches were built in the new gothic style, but incorporating the original dressed Saxon stonework at their base. Indeed, the arch supporting the later medieval west tower might also be Saxon in origin – narrower than later designs. The archaeologist, Warwick Rodwell, posited a grand cruciform church, a now lost apse at the east end and smaller apses off the east walls of both transepts.

The beautiful north door would offer the most exciting part of the story. The moulding on the jambs and arch looks Saxon. But the door had been moved; Rodwell’s excavations found it originally sat further west and was moved closer to the transept in the early 13th century. So in 2003 dendrochronologists were called in, a series of microcores establishing the door’s timber as from trees felled around 1034 – slightly after Cnut’s foundation, but perhaps consistent with a door being fitted within his reign. This would also make the door and its metal fittings – still used as the church’s main entrance – the oldest in the country, pipping the much better known Chapter House door in Westminster Abbey (fitted under Edward the Confessor in the 1050s). Macabrely, the door was also coated with a tanned leather which was reputed to be the skin of a Viking slain for violating the church; modern tests were also used here, which found it was (much more prosaically) an oxhide.

As ever, this isn’t the end of the story; the most persuasive counter-argument being made by Eric Fernie in 1983 which compared the door’s upper moulding to a Norman church in Caen, dating it later than Cnut’s post-Assandum church. If correct, for me this in turn returns us to our initial profound mystery – what is an enormous Saxon church doing in this tiny Essex village?

Discussions of angle rolls and sapwood rings moves me well beyond any pretence at expertise and only able to hold my hands up in ignorance; suffice to say the church’s identification with Cnut remains intriguing and far from conclusive, but also a fascinating excuse to read further into the last hurrah of Danish conquest in the British Isles. But little Hadstock’s importance goes deeper still.

A man called Botolph

The 1973 excavation found something else exciting beneath the late Saxon building. For the lower parts of the walls – still visible in the nave – and extensive remains below the floors date to a much earlier church, as early as the 7th century. Discolouration on some of the stones suggested destruction by fire. Dating of charred timbers found in the dig indicated this firing could have been the late 9th century, contemporaneous with the Great Heathen army’s rampage and sacking of the monasteries at Ely, Peterborough, and Thorney in 869.

So what was this church? It’s dedicated to St Botolph (Botwulf), an early Saxon missionary referenced in the Anglo-Saxon chronicle as having built a church at ‘Ikenho’ (Yceanho) in 653/654. This is usually associated with another St Botolph’s church in today’s Iken, on the Suffolk coast; but this has – again – no remains of a Saxon structure, although a reused Saxon cross was found in the tower’s structure during a modern renovation.

You may have seen where this is going. There are some credible suggestions that Botolph’s Ikenho, which was also recorded as destroyed by the Great Heathen Army, may have been today’s Hadstock.

Firstly, the name. Ikenho/Yceanho may related to the Iceni – the East Anglian tribe of Boudica – who were active in East Anglia and gave their name to the Icknield Way, the ancient trackway which I took on my walk to the village.

Secondly, the church itself. Later hagiographical sources refers to Botolph founding his church in a valley with a stream, far from the sea; which fits Hadstock and not coastal Iken. Furthermore, St Botolph’s in Hadstock is the only one known to have held the charter for a fair in the saint’s name – a designation apparently predating the Norman conquest – which should denote considerable significance in its relation to the saint. Another clue from the medieval Liber Eliensis, a chronicle of Ely abbey, refers to Hadstock (then called ’Cadenho’) as founded by St Botolph – and where he lay in rest (“…ibidem quiescente…” III.90). And there is the matter that Hadstock and St Botolph’s Ikenho were likely both destroyed by the Great Heathen Army.

Thirdly, the 1973 excavation found an unusual grave in the south transept. Raised above the Saxon floor level, and inside the transept itself, it must have held someone of status and perhaps subject of veneration (maybe in the apsidal chapel annexed to the transept’s east wall). The grave was empty, which raised an interesting possibility. Sources record that Botolph’s Ikenho church and his grave lay in ruin until 970 when Bishop Aethelwold of Winchester exhumed Botolph’s relics from the ruined chapel where they had been laid to rest – leaving an empty high-prestige grave.

So – is Hadstock the site of Botolph’s original monastery, and his burial place? Tantalisingly, here the trail runs cold – as with the Cnut identification, there’s no knock-out blow, and there are scholars who have railed against the identification (e.g. Martin 1978). If it were Botolph’s 653/4 foundation, the stonework we see in the lower nave could be from the original church – the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle uses the Old English verb ‘timbran’, which is usually translated as ’to build from timber’ but is regularly used for non-wooden buildings such as burh earthworks, and even metaphorically in religious and philosophical tracts; while St Peter-on-the-Wall, a church 50 miles away at Bradwell-on-Sea likewise dated to 654, was built of stone by Botolph’s contemporary Cedd. And if that is right – and it’s an extremely heroic if – it would make this church in little Hadstock the second oldest in England, level with the much more famous St Peter’s and pipped only by St Martin’s in Canterbury (founded by Augustine in 594).

So what?

A little bit of research on an unusual church in a small corner of Essex which, before this project, I had never come across; and which blossomed into a trawl through archaeological reports, saintly hagiographies, Latin and Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, and some great bits of local history.

None of the above claims to prove anything historical – and the two exciting identifications may be wrong. But what I hope it does prove is how the crux of investigating just one church (of more than 40,000…!) can be such a rewarding rabbit hole; and a good amount of affirming distraction at a time when it’s very needed.

(Thanks in particular to Llewelyn Morgan, who dictated valuable parts of Pevsner to me down the phone while I sat in a Caffe Nero)

Further Reading

St Botolph’s Church Hadstock – a Short History and Guide (no date, available at the church)

Warwick, R., Under Hadstock Church (1974)

Fermie, E., “The responds and dating of St Botolph’s, Hadstock”, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 136, pp.62-73 (1983)

Martin, E.A., “St Botolph and Hadstock: a reply” Antiquaries’ Journal, 58, pp.153–59 (1978)

Pevsner, N.; Bettley, J. Essex: Buildings of England, Pevsner Architectural Guides (2007)

“Hadstock Church: Opening a door on Saxon History”, The Saffron Walden Historical Journal, 6 and 9 (2003 and 2005)